Sometimes focusing our attention feels impossible. As soon as we settle down at the computer, or into a conversation, we can find ourselves darting around, proverbially switching channels back and forth. We can start to wonder, “Do I have ADHD?”

Today we’re going to look at what actually happens in the brain when we have trouble focusing. Whether or not you’ve been diagnosed with ADHD, understanding how our brains pay attention will help you make changes so you can hold attention in a healthy way.

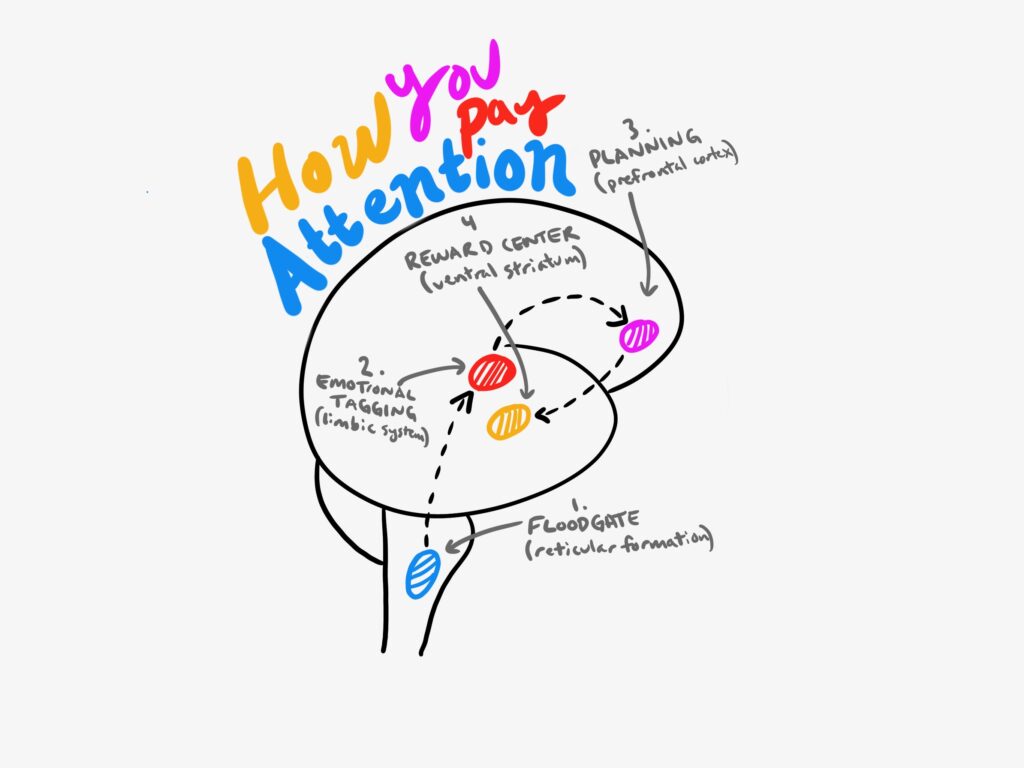

Here’s what’s happening in the brain when you focus attention

Your mind is constantly receiving thousands of inputs every second – from your skin and muscles (the uncomfortable chair you’re sitting in), from your ears (that air conditioning in the background), from your stomach (it’s been a while since breakfast!), from your social awareness (I’m surrounded by people right now) and from communication from others (this article teaching you about ADHD), among other things.

It’s a wonder that your mind can focus its attention at all. It needs a way of organizing a whole world of constantly changing pieces of information so it can keep you safe. The way the mind does this is really important: it focuses your attention on threats so it can resolve them and feel safe again.

Attention Neurology:

- The floodgate. First, your mind measures how much information it wants to take in. Picture the difference between eating an apple on an empty stomach, versus eating an apple after an ice cream sundae. On an empty stomach, you might taste intense, complex flavors from the apple. After an ice cream sundae, however, it might hardly taste sweet. This is the job of the reticular formation. It measures how much stimulation (excitement) your brain can take to keep you somewhere between feeling bored and overwhelmed.

- The emotional stamp (limbic system). Next, the information is stamped with emotion. Like a message coded by urgency (?), the limbic system tags how important this new information is to your safety and prepares your body to respond. When you feel a tinge of stomach tension at receiving an email from your boss, it’s because your limbic system told you there’s a threat to your safety: you could be in danger of being dismissed or abandoned. Your entire body responds right away, changing your heart rate, blood flow, and attention so you can be safe.

- The planning center (prefrontal cortex). Imagine a rider on top of an emotional elephant. The elephant is our emotional brain, charging haphazardly away from danger and toward safety. The rider (prefrontal cortex) has to decide how to direct the elephant’s energy. The rider is a bit frustrated with the elephant’s erratic impulses! He tries to navigate the elephant in a straight line toward the main goal of connection and safety, taking into account social norms, past experiences and outcomes, contextual cues, and other emotions in ourselves and others. The rider considers two main voices: the Behavioral Activation System (BAS) and Behavioral Inhibition System (BIS). The BAS is like a forward-thinking rider. She decides how to direct the elephant’s energy down a certain path. It’s good at planning logical steps that help it achieve goals and satisfy needs for connection and safety. The BIS is like a cautious rider. She pulls the reigns to keep the elephant from running wild. She’s concerned with holding back on emotional impulses, trying to steer clear of social stigma, rejection, and shame.

- The reward center (ventral striatum). Think of a party at the end of a marathon: the runner endures enormous pain, finally crosses the finish line, and feels immense relief and pleasure. He completes the goal and finally wins the needed sustenance and support. His brain is flooded with dopamine, which slows his heart rate and relaxes his muscles. Next time he runs the marathon, his mind will stay on task, knowing the reward at the end.

To summarize,

Whenever your mind receives an input, it first evaluates its strength and connection to your survival, and you feel your body become ready to respond. Your prefrontal cortex then plans what to do – to either resolve the need or suppress it and stay on task toward the current goal and reward.

So let’s say you’re writing a brief.

When the project first came up, you felt excitement. Your limbic system tagged the project as important because of your long term goal to make money – and more importantly – be included in a community and avoid abandonment (safety).

Right away, you felt engaged with the project. Your BAS was organizing your excitement and planning different behaviors to get closer to your goal. You might sit down and outline your project.

BUT THEN – you get a text. This time it’s from your partner. It says, “I didn’t feel great about how we ended last night.” You feel another rush in your body. This time, it’s not excitement but anxiety. Suddenly the project is out of your mind. If you pay attention, you might notice your BAS organizing yourself differently: “If I don’t respond right away, will they think I don’t care?” You feel the pain of an attachment strained. Your BIS then struggles to evaluate. How important is this new goal in relation to the project? How do I weigh my long-term survival against this immediate conflict? Should I stop working on the project now and call my partner?

Just then, a co-worker asks you a question. “Did you see the game last night?” Your mind is now balancing a few different bids for attention. This is where you start to feel your mind struggling to focus.

Attention problems can be caused by a few different areas

If you struggle with holding attention, there may be a problem with one or several of the brain areas we mentioned earlier.

Now, before we jump ahead, it’s important to note that the structure of your brain is the combination of your genetics, past experiences, and present experience. For the sake of simplicity, let’s say about 50% of your brain’s structure is caused by your genetics, and 50% is the result of your environment. Why is this important? Too many people confuse “brain structure” with organic/genetic causes. If you have a weakness in your reward pathway, making it difficult to feel pleasure when you achieve a goal, it might be because of an organic/genetic difference, or it might be due to the way rewards have been handled throughout your life. Both genetics and experience alter the structure of your brain.

With this in mind, let’s look at different ways you might be experiencing problems with attention.

Is my focus issue a “floodgate” problem?

Sometimes our problems in attention have to do with how stimulating our environment is. Each of us has a “Goldilocks” zone where we aren’t too bored or overwhelmed, where things are just right and we feel engaged. For some of us, reading a book doesn’t hold our attention. It feels boring and it’s hard to pay attention. For others it feels just right: a quiet room, a book, low light is the perfect amount of stimulation to hold our attention. This has to do with our floodgate, the reticular formation, that is monitoring the volume of the world around us.

Extraverts might need to add music, bright light, or tap their feet to raise the volume of the reading so they can pay attention. Introverts tend to feel overwhelmed by this idea! They might struggle to engage with reading in a loud room, needing to pull away into a quiet room to read.

How about you? If you struggle with attention, it’s possible that you’re either overwhelmed (“I can’t focus! It’s too much!”), or bored (“I can’t focus! It’s too mind-numbing!”).

Try adjusting the volume of the task by adding or removing stimulation.

Add music or exercise beforehand to make a boring task more engaging. Retreat to a quiet space away from distractions to make an overwhelming task more engaging. These volume adjustments help us focus our attention.

Is my focus issue an emotional problem?

Attention is anything but a cognitive task. Attention is mostly an emotional task that begins and ends in our brain’s limbic system (emotional center). Our emotional state is the elephant that moves our attention toward a goal to help us feel safe and connected. If anxiety and dread overwhelm you, writing a report is going to be incredibly difficult. Your mind will keep redirecting, over and over, toward your emotional state.

If you’re depressed, your concentration suffers. Your mind will keep redirecting toward your sadness. But if your mood improves, so does your attention. You’ll even find yourself being more creative at solving problems.

If you’re anxious, your attention suffers as well. PTSD significantly affects focus and attention. Why? When your world feels unsafe, your mind has to keep redirecting attention.

So what do we do? Trying to force ourselves to pay attention when we’re emotionally overwhelmed is like a tiny rider on top of that emotional elephant: it’s not gonna do much good.

The only solution is to help ourselves feel safe.

Regulating our emotions, and soothing ourselves is the first step. Sometimes this is as simple as reminding yourself of a loved one who cares about you. Other times this is about addressing emotional patterns in therapy.

Is my focus issue a planning problem?

After you feel an emotion and your body gets ready to act, your prefrontal lobe starts to plan how to achieve the goal. Sometimes it means telling yourself to stop working on other goals. Other times it means taking time to plan out each step you need to get to your goal. How you manage these two voices (BAS and BIS) has a lot to do with how others in your life have helped you achieve goals. For example, picture a child who’s trying to stack blocks, and gets frustrated. The parent who swoops in and stacks the blocks for the child, while well-intended, doesn’t help the child learn the planning skills they need. A parent that shows the child step by step how to stack the blocks will help strengthen the child’s frontal lobe, nurturing their ability to set and achieve goals.

In the same way, if we struggle with attention problems today, it might be a planning issue. Maybe it’s hard for you to take a moment to stop and plan the steps to get to your goal. Maybe it’s hard to say “no” to something you want so you can get the larger goal. This can be a powerless feeling – like there’s no way to move forward. This is where we switch attention – largely to avoid feeling powerless.

If this sounds like you, you’ll need to take the time to outsource this part of your brain to a checklist.

You might try taking time, before the start of the task, to outline the steps you’re going to need to take to get it done. You might also benefit from therapy. Addressing and understanding the feelings you have about setting goals can help you feel focused and in control again.

Is my focus issue a reward problem?

Sometimes our problem with holding attention has to do with a lack of reward. If we can hold our attention well, it’s because we know that by planning and holding out attention on a task, we’ll feel good again, relieved. Think of an Olympic athlete: they strain to hold their attention hour after hour because of the promise of winning gold. Think of a parent who spends an hour learning to bake a cake for their child: they hold their attention because of the promise of vicariously feeling their child’s joy. We hold our attention when we know there will be a reward.

For some of us, there’s no promise of reward. Maybe your own childhood involved a depressed parent who struggled to “light up” when you achieved a goal, and you felt like you could never make them proud. This experience lays pathways in your frontal lobe that influence how you experience daily tasks. Or maybe you’re living alone, so cleaning your house goes unnoticed. Maybe you have a preoccupied boss who doesn’t reward your hard work. In each of these situations, it will be a struggle to hold attention on a task, because your mind struggles to see the reward it’s working toward.

If this is the main obstacle to holding your attention, you might tend to feel tasks are meaningless, hopeless, or boring.

How do we help this issue? Some suggest giving yourself a treat when you complete a task: like rewarding yourself with chocolate. You’re welcome to try that if it works for you! For many people, however, this will only get you halfway there. The dopamine (reward) area of the brain is built around social rewards. The strongest reward we can receive is another person’s praise.

If you struggle with reward pathways, don’t think of giving yourself a treat; think of making the task meaningful.

How can you link the task with how it will contribute to your feeling connected and helpful in the world? Is there a way to include others in the task so you can receive feedback and praise? Is there a way the task could help someone else? How could you change the task to heighten these aspects?

So, do I have ADHD?

ADHD requires a diagnosis, something you can get by scheduling an assessment with one of our psychologists. Why a psychologist? Because too often, we diagnose ADHD whenever we spot an attention problem, without considering other factors, such as emotional health, life stressors, introversion/extraversion, etc.

Whether or not you have ADHD, you can rework your relationship with attention. Whether it’s about reducing/increasing the input (floodgate), regulating your emotion (making it more meaningful or less panic-inducing in the limbic system), taking more/less time to plan, or giving yourself more meaningful rewards, there are ways we can shift gears to pay attention, regardless of your diagnosis.

The effort it takes to hold attention can be frustrating. Talk with one of our therapists today. We’ll help you find your way to feel on top of your life again.